Minimum Wages: Few Benefits, Many Consequences

President Obama’s recent State of the Union address was the culmination of months of advocacy from Democrats and activists for a higher minimum wage. The President proposed a raise to the minimum wage for federal contractors by executive order to $10.10 per hour and called on Congress to raise the national minimum wage for all workers to the same mark, along with indexing it to inflation. A raise of the national minimum wage was framed as giving low income workers the “living wage” they deserve and fighting perceived growth in income inequality in America. Though the President’s proposal is well intentioned, it faces many ignored unintended consequences: higher unemployment for the young, unexperienced and low-skilled workers. Moreover, the unemployment caused by a higher minimum wage has long lasting—perhaps permanent—effects on the individuals a minimum wage increase is designed to help the very most.

The Case Against The Minimum Wage

The case that a higher minimum wages reduces employment opportunity is fairly intuitive. Minimum wage laws make labor agreements illegal for employers who want to hire employees who fall below the legal minimum wage. The laws effectively force employers to only employ a worker if the net value that that worker can add to the business is over the minimum wage hurdle—say $7.25 or $10.10. Businesses do not hire workers as a charitable endeavor, but instead employ them to raise their profitability with higher output or better service. The higher the wage, the fewer entry level workers a business is able to employ without losing money on the deal. As a result, many employers are unwilling to put their company at risk by acquiring workers they cannot afford, which explains why the job market tends to contract when the minimum wage is increased.

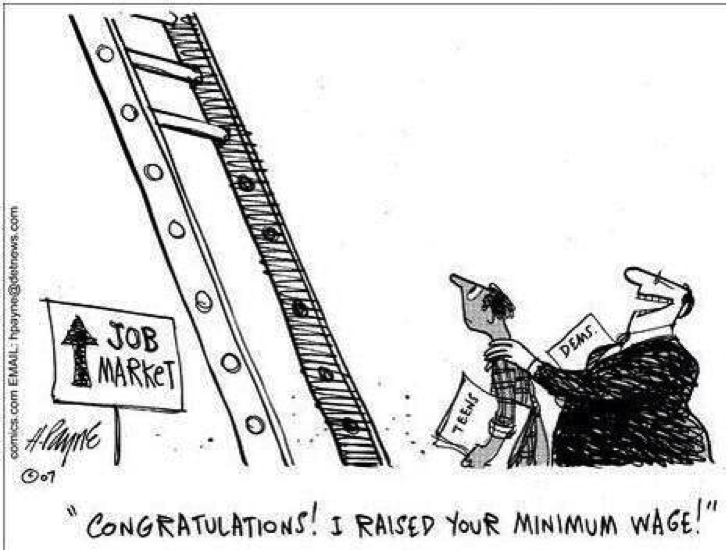

This great comic by Henry Payne illustrates this idea pretty clearly:

For workers who earn $7.25 now but create enough value to warrant a wage of $10.10, their job may very well be safe. But for those young, inexperience, low-skilled workers that are struggling to create $7.25 for their business, they may be on the chopping block. Moreover, those workers currently unemployed or just entering the job market will find that they will have to convince an employer that they are worth $10.10 an hour, instead of $7.25 for whatever their skill set warrants. For those workers who either aren’t yet skilled enough to warrant $10.10 an hour, or able to convince an employer of their merits at that wage price, they will face unemployment.

Outstanding videos from the Institute for Humane Studies’ Learn Liberty project and the Foundation for Economic Education, seen below, explore this argument in greater detail.

The Minimum Wage in Practice: The Consensus of Academic Studies

This argument is not just conceptual. Despite the existence of a few controversial studies suggesting that minimum wage laws may not harm employment, academic literature in economics overwhelming suggests that minimum wage laws do indeed kill jobs. Dr. David Neumark and Dr. William Wascher find in their seminal treatise, Minimum Wages, that a very strong majority of research suggests that higher minimum wages are correlated with lower employment. Dr. Bryan Caplan adds to this research consensus by pointing out that a wide variety of labor economic research further makes the case that minimum wages kill jobs.

Also, consider briefly the implication that a minimum wage increase would not lead to higher unemployment. According the center-left Economic Policy Institute, “an increase to $10.10 would either directly or indirectly raise the wages of 27.8 million workers, who would receive about $35 billion in additional wages over the phase-in period.” The notion that over a very short amount of time, nearly 28 million workers will receive raises totaling nearly $35 billion dollars, and an insignificant amount companies will go out of business, cut jobs, or freeze hiring is quite frankly absurd on its face.

Who Are Minimum Wage Workers?

What the President and minimum wage increase advocates often overlook in their framing of the debate is the actual profile of minimum wage workers. As Cara Sullivan pointed out in a recent American Legislator blog post:

More than 40 percent of these young earners are enrolled in school during non-summer months, and for 79 percent, it is a part time job. For many young earners, their wages are supplemental spending cash, not household income.

Perhaps the possibility of fewer available employment opportunities would be more palatable if increasing the minimum wage actually helped impoverished Americans. However, the benefactors of an increase to the minimum wage—those who currently hold a job and earn the minimum wage—are more than likely not living in poverty nor supporting a family on minimum wages alone. Over half, 50.6 percent, of minimum wage earners are between the ages of 16 and 24, with an average annual family income of $69,500. Of the adults 25 and older earning the minimum wage, 75 percent of them live above the poverty line and have an average family income of $42,500 a year.

A recent Forbes post by Jeffery Dorfman further points out that “only about 1.1 percent of all workers over 25 and 0.8 percent of all Americans over 25 earn the minimum wage.”

What Do Low-Skill, Low-Experience Workers Really Need?

Minimum wage workers are largely young, low-skilled, and part of a household earning multiple incomes. What these workers need is the best income they can find while building up their employment profile, such that they can find a better job. Minimum wage work is largely temporary work en route to something better.

To dig out of this economic hole that many millennials and low-income Americans have found themselves in, they need the career building blocks that internships and entry-level jobs provide. In these building-block jobs, workers can gain educational training, demonstrate work ethic, display ingenuity, prove honesty, develop important references, and generally reduce the uncertainty around their value as an employee, even if the internship or entry-level job is not relevant to a subsequent job for which an employee is applying. This makes them more productive and consequently means employers will pay them higher wages. As such, these entry-level jobs are a direct pathway to better pay; not a ticket to permanent status in the lower-class as some suggest.

Entry level jobs also help young workers avoid the fate of long-term unemployment. Evidence suggests that remaining unemployed for six or more consecutive months makes it extremely difficult to get a job, even for skilled and otherwise well-qualified employees. To stress the importance of preventing long-term unemployment, consider a recent study published by Rand Ghayad of Northeastern University and chronicled in an Atlantic Magazine article. In short, unemployment for six or more months drastically lowers the chance for a job seeker to find employment, even if that job seeker is otherwise well qualified. In fact, long-term unemployment weighs more heavily on the likelihood of getting a job application “call-back” than relevant experience.

Internships and entry level jobs allow workers to avoid this long-term detachment from the labor force, or climb out of the despair of long-term unemployment, which cripples their employment prospects. As such, those advocating for a higher minimum wage are directly harming those they set out to help. Minimum wage laws act as price controls and reduce the number of entry level jobs and internships available, which deeply—if not permanently—harms those priced out of the labor market.

What policymakers should truly be considering when they look to help those with low incomes is how to advance them in society to jobs that come with a higher income. Since minimum wage laws only raise the wages of some workers, while directly harming many other workers attempting to work their way up the career ladder, a minimum wage increase is not a sensible policy. A sensible policy to help low income workers would involve offering low income workers direct assistance or better yet, improving the national policy environment with free market economic reforms that boost job growth and income growth.

Can’t Businesses Just Sacrifice Profit to Pay a Higher Wage?

It’s a mistake here to think that businesses can simply pay workers more, employ the same number of workers, and simply cut down on profits or executive compensation. This notion ignores that many small and medium sized businesses are on the edge of profitability and simply absorbing wage increases would put the firm out of business. Even for larger, national firms that employ a significant amount of low income workers, labor prices are one of their primary expenses and a large minimum wage increase, like the 40% increase associated with moving from $7.25 to $10.10, could harm the firm’s profitability.

Even if the firm doesn’t go bankrupt, the damage to its profitability could harm its ability to attract investors. Investors won’t invest in industries that are barely profitable, so they will stop investing in businesses that employ a lot of low skilled workers, which will in turn hurt low skilled workers. Businesses may also respond by “trading labor for capital,” and installing machines that can help or entirely do the jobs that were previously performed by low income workers. And if a business plan is to pass costs on to consumers, business may see sales go down, forcing many businesses into bankruptcy or lower profits. And even if businesses can effectively push price increases on to consumers, an increase in consumer prices hurts people, particularly poor people.

Is the Minimum Wage a Public Subsidy to Employers Paying Low Wages?

Similarly, the notion that businesses are “receiving corporate subsidies” in the form of social assistance payments to their low income workers is a backwards notion of social obligations. As a society, we should support the employment and productive contribution of as many able-bodied individuals as possible to the economy. If there is any duty for a citizen to be lifted above a given earnings threshold, it arises from a social obligation that society as a whole should bear. Georgetown University philosopher Jason Brennan has compellingly pointed out as much in a recent post at the Bleeding Heart Libertarian blog. The correct level of social assistance is a topic worthy of much debate and is beyond the scope of this post, but what is clear is that the morally desirable arrangement is for society—not employers—to bear the obligation of providing a “living wage” if its justification arises from a moral obligation. As such, firms paying low wages are not receiving any type of reprehensible public subsidy, but instead providing social value by creating entry level jobs that put young, inexperience, or economically displaced workers on the path to a fruitful career.

Conclusion

A minimum wage increase will certainly offer direct, visible benefits to those workers that are able to avoid layoff, but will offer grave harm to those who are laid off or unable to find work as a result of a higher minimum wage. The benefits of the policy are greatly outweighed by the harm many workers will face as a result of current unemployment and future damage to earning potential because of the harms inherent in unemployment, particularly if the unemployment becomes long-term. There are many policies better suited to helping low income workers, most notably, fundamental economic reform that offers real, sustainable job and income growth. Policymakers should focus on policy reforms that avoid the consequences associated with a minimum wage increase.