Smart is The New Tough: Prison Reform

Harsh drug sentences were once thought to be the best solution for getting illegal drugs off the streets. While the results of these policies are debatable, it’s indisputable that today our prisons are full of non-violent drug offenders. According to the Federal Bureau of Prisons, nearly fifty percent of federal prison inmates are incarcerated for drug-related offenses. The numbers have grown dramatically after increased sentencing legislation was enacted in the 1980s. Many inmates are addicts and will unfortunately return to drugs after they are released from prison. It is for this reason that states are offering drug and alcohol treatment instead of incarceration. States are working to address addiction, which is often the root of criminal behavior, with evidence-based programs like drug courts and swift and certain sanctions.

http://www.pewtrusts.org/~/media/Post-Launch-Images/2015/02/federal_prisons_fig1_PSPP.jpg?la=en

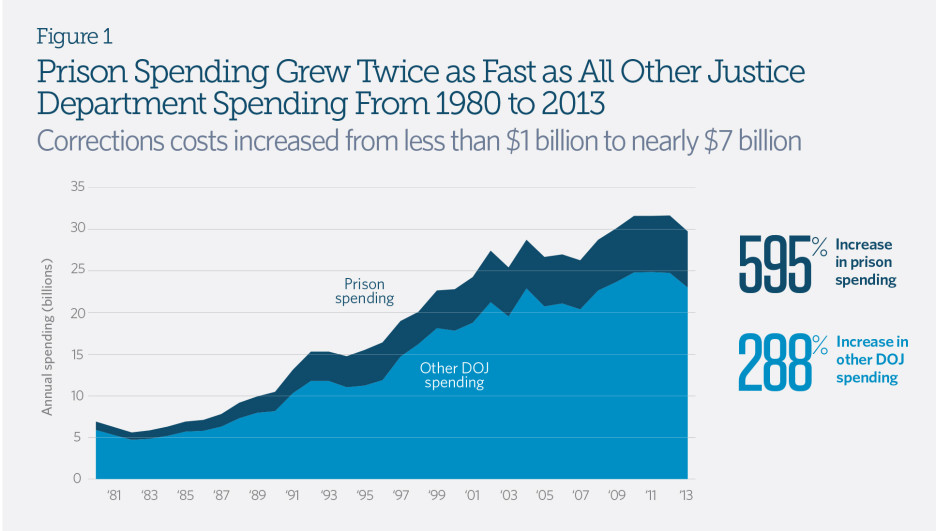

Seventy-seven percent of those convicted of drug offenses are rearrested within five years of their release, according to The Bureau of Justice Statistics. It is clear that our current system is not addressing the problem, and is exceedingly expensive. For example, the cost for a year of treatment for heroin addiction is $4,700, while the average annual cost of incarceration cost is $31,603 per inmate.

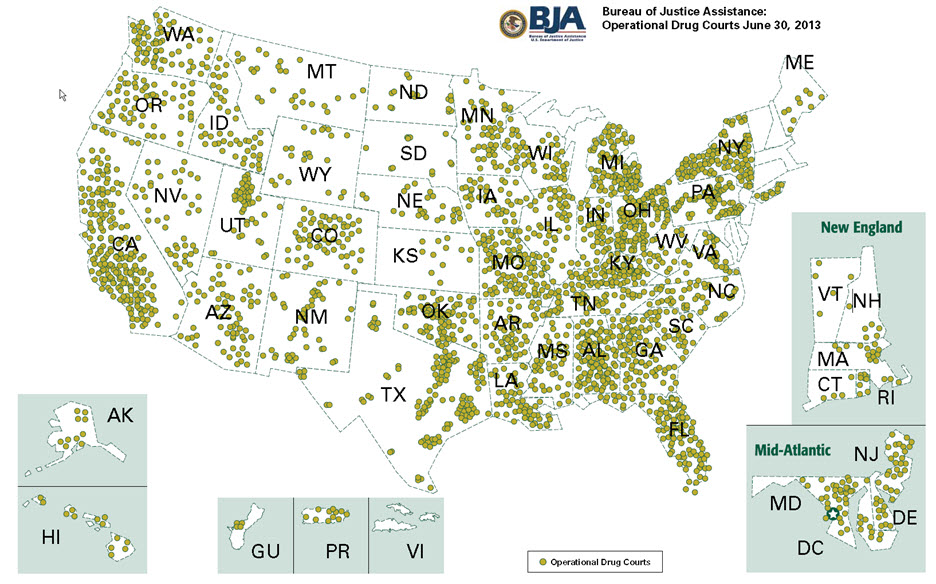

One well-used solution is drug courts. More than 3,400 drug courts currently exist.

Drug courts are an intensive program where a judge and community corrections officers closely monitor an individual’s progress staying drug-free and becoming a productive member of society. Individuals in drug courts are given random drug tests, meet often with the judge and are given sanctions or rewards based on their performance.

Drug courts, depending on the state, offer pre-prosecution or post adjudication programs. When pre-prosecution offenders successfully complete the drug court program, they can have their charges dropped. In post-adjudication programs the defendant is charged, but they have the ability to reduce their sentence, or have it expunged once they complete the program.

According to the National Association of Drug Court Professionals (NADCP) the average recidivism rate for graduates of drug court was only twenty-seven percent after two years – compared to the average seventy-seven percent recidivism rate. All of these options can help a drug user to become a contributing member of society, yield lower rates of recidivism, spends less taxpayer money and prevent jails from becoming increasingly overcrowded.

Take the story of Donny Myers, whose troubles began after his father’s death. Myers turned to alcohol at the age of eleven and moved on to marijuana before becoming addicted to methamphetamines. By the time he was an adult, he was spending the majority of every year in prison for different criminal offenses. In 2010, Myers was sent to a drug court and mandated to undergo a 16-month recovery process. Myers, with the help of his family and a dedicated judge, completed the program and is finally sober.

Similar to drug courts, ALEC members support Swift and Certain Sanctions programs, which require immediate sanctions for those who violate parole or probation. These commonsense programs say that if you violate the terms of your supervision, such as missing a meeting or failing a drug test, there will be immediate consequences that match the level of the infraction. Both drug courts and swift and certain sanctions have proven to reduce recidivism for drug offenders.