Paris Climate Change Talks: How Did We Get Here?

We examine past international activities that sought to address climate change, and illustrate how the situation arrived where it is today

The United Nations (UN) has been trying to address the climate change issue for the better part of 20 years now. In some respects, the Paris summit will be the culmination of at least two decades of work. However, as will be explored further next Monday, many suggest Paris is only the first step of a much longer process that will have to constantly be built upon as circumstances (e.g., technological advances, costs, etc.) change.

In thinking about what might ultimately arise from the Paris talks, it is worth examining past international activities that sought to address climate change, which will hopefully illustrate how the situation arrived where it is today.

United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (1992)

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) is an international climate treaty developed at the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED). The framework is not considered legally binding in the sense that emissions limits for greenhouse gases are not established, nor does it contain any enforcement mechanisms. Rather, the agreement lays out a framework of protocols for how future climate treaties should be developed.

Article 2 of the UNFCCC identifies the objective of the framework (and, by extension, all succeeding agreements) as the “stabilization of greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that would prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system.”

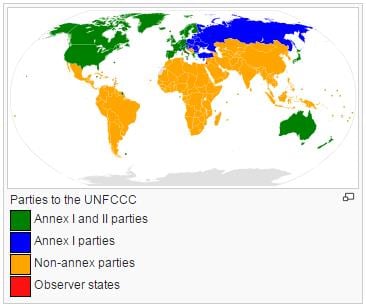

The UNFCCC also classifies nations of the world into three categories, according to their deemed climate responsibilities and ability to make changes:

- Annex I Parties include the industrialized nations that were members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) as of 1992 and nations with economies in transition (EIT). EIT parties include Russia and many nations in eastern and central Europe. There are 43 Annex I Parties, including the U.S.

- Annex II Parties consist of the OECD countries but none of the EIT Parties. Significantly, these countries are required to provide financial resources to developing countries so that they may be able to limit greenhouse gas emissions, themselves, and adapt to the effects of climate change. Furthermore, these countries must help develop and transfer new energy technologies to EIT Parties and the developing countries. There are 24 Annex II Parties, again including the U.S.

- Non-Annex Parties include all other countries. These are generally developing nations the UN believes are the most vulnerable to the effects of climate change, including those countries that heavily rely on fossil fuels and may be negatively impacted economically if forced to limit emissions.

Given its classification as an Annex I and II Party, the U.S. is one of the 24 countries expected to significantly curtail emissions, provide financial assistance to developing countries and develop new energy technologies as a part of any international climate agreement.

Kyoto (1997)

The Kyoto Protocol is an international treaty broadly outlining emissions reduction targets for participating countries. In accordance with the philosophy of the UNFCCC, the protocol takes into account each nation’s unique circumstances and their ability to reduce emissions. The predominant features of the protocol are the legally-binding commitments made by Annex I Parties to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. Non-Annex countries were not required to meet any reduction targets. The protocol also created the Adaptation Fund, which would be used to finance projects and programs in developing countries to mitigate the impacts of climate change.

The U.S. signed the protocol in 1998 during the Clinton presidency, but in order to become legally binding, the treaty had to be ratified by the Senate. Notably, a year earlier in 1997, the Senate passed by a vote of 95-0 the Byrd-Hagel Resolution, which stated opposition to any agreement that did not also require developing nations to make emissions reductions. Given this apparent opposition, President Clinton never submitted the treaty to the Senate for ratification. President Bush opposed the protocol and, upon his election, similarly did not submit the treaty to the Senate. Despite this setback, the protocol was enacted in 2005 for the countries deciding to participate.

Copenhagen (2009)

Given the lack of support and inherent shortcomings of the Kyoto Protocol, international officials descended upon Copenhagen for COP 15/CMP 5 with the intention of developing a framework to be implemented for the year 2012 and beyond. However, attendees failed to develop any binding agreement. A major point of contention was how to treat China, the world’s largest emitter of greenhouse gases, albeit a Non-Annex party. What ultimately came out of Copenhagen was a document drafted by five countries – the United States, China, India, South Africa and Brazil – which delegates merely agreed to “take note of.” The accord had a number of shortcomings; most notably, it was neither legally binding nor actually set any real emissions reduction targets. Nevertheless, in response to Copenhagen, President Obama in 2009 attempted to pass cap-and-trade legislation but was unable to do so, despite enormous Democratic majorities in both chambers of Congress.

Since Copenhagen

Without participation from the U.S. and the developing world, support for Kyoto began to unravel as the initial 2012 benchmark drew near. In 2011, Canada withdrew from the agreement entirely. The Protocol was extended in 2012 to last until 2020, but a handful of countries – notably Japan, New Zealand and Russia – declined to participate any further. The protocol is still in force, but countries currently participating represent roughly 15 percent of annual global greenhouse gas emissions. In 2012, delegates also solidified plans to again attempt to develop a successor to Kyoto by 2015, which would be implemented by 2020.

This is the situation as it stands today. International negotiators are extremely desperate to achieve a binding, universal climate agreement and informal pre-Paris negotiations are currently underway.