Jonathan Williams Testimony on North Dakota Tax Reform

On November 13, 2019, ALEC Chief Economist and Executive Vice President of Policy Jonathan Williams was asked to testify in front of the North Dakota Legacy Fund Earnings Committee in regards to state fiscal policy, including income tax rate reductions. His written remarks can be found below.

The evidence on state fiscal policy

Thank you, Mr. Chairman and distinguished members of the committee for the invitation to speak today. I appreciate the opportunity to present our non-partisan research and analysis on income taxes and economic competitiveness in the states.

As you may know, ALEC is the nation’s largest non-partisan, voluntary membership organization of state legislators. Comprised of nearly one-quarter of the country’s state legislators and stakeholders from across the policy spectrum, ALEC members represent more than 60 million Americans and provide jobs to more than 30 million people in the United States. We believe all Americans deserve an efficient, effective and accountable government that puts the people in control.

Today, I will provide a review of the economic literature on various forms of taxation and their impact on growth and wellbeing.

A review of the academic evidence on taxes and economic growth

A large volume of academic literature makes it clear that all taxes negatively affect economic growth. A Tax Foundation survey of 26 peer-reviewed studies since 1983 found that 23 indicated a negative relationship between taxes and economic growth, while the other three found no relationship at all.

However, not all taxes are created equal, and some harm economic growth more than others. Scholars at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) using a panel of data from 21 nations, found that corporate and personal income taxes are far more distortionary and harmful to economic growth than taxes on consumption, like sales taxes. They controlled for various factors, including measures of physical and human capital accumulation, population growth, and time and country-specific effects. Researchers also controlled for the overall tax burden in each country as a share of GDP. This allowed them to isolate the effect of different types of taxes based on the share of tax revenue that comes from each source. Their results indicated that a 1% shift of tax revenues away from income taxes (both personal and corporate) would increase GDP per capita by between 0.25% and 1% in the long-run.

Another important finding of this study was that progressivity of personal income taxes substantially reduces economic growth when compared to flat-rate tax systems. The OECD authors found even more support for their results by looking at industry and firm-level measures of investment and productivity growth. They found that corporate taxes, both in terms of the rate and depreciation allowances, reduce growth of investments and productivity. They write: “a reduction in the top marginal personal tax rate is found to raise productivity in industries with potentially high rates of enterprise creation.”

Annually, I co-author the national economic study, Rich States, Poor States: ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index. Together with my co-authors (Reagan economic advisor, Dr. Arthur Laffer and Stephen Moore), we analyze how economic competitiveness drives income, population and job growth across the states. Rich States, Poor States adds to a growing body of evidence that taxes matter, and some taxes matter more than others. For many years, our research has warned against an over-reliance on income taxes – on both personal and business income.

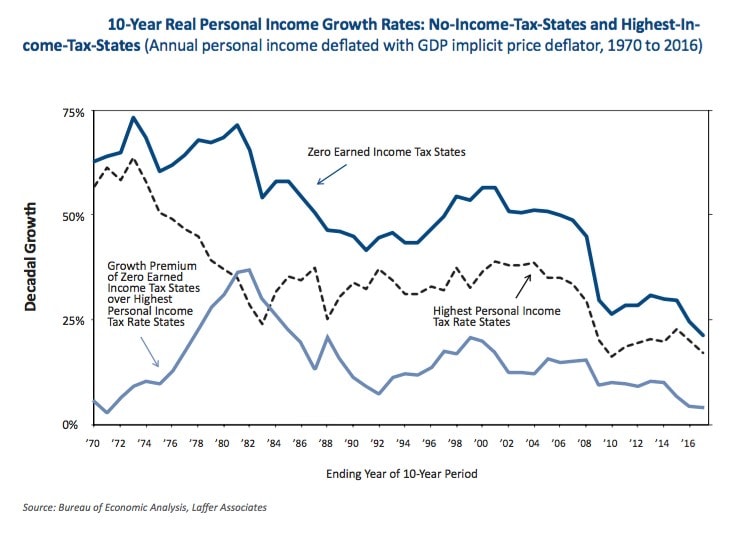

Obviously other factors, including right-to-work status, regulatory environment and makeup of state economies clearly matter for these statistics; but these general trends are reflected decade after decade for the past 50 years. The graph below highlights the economic growth premium of states with no personal income tax when compared to those with the highest personal income tax rates.

Data from the 11 states that adopted a personal income tax between 1961 and 1991 are also illuminating. These states include West Virginia (1961), Indiana (1963), Michigan (1967), Nebraska (1968), Illinois (1969), Maine (1969), Rhode Island (1971), Pennsylvania (1971), Ohio (1972), New Jersey (1976) and Connecticut (1991). In the years following adoption of the tax, in every one of these states, population, employment, personal income, gross state product, and state and local tax revenues all declined relative to the rest of the nation.

The reasons why income-based taxes are economically damaging to states range from the adverse economic effects of the taxes, to purely public finance objections, such as the volatile nature of income tax revenues.

Income taxes and revenue volatility

Reliance on income-based taxes is especially troublesome for states during difficult economic times. Taxes on corporate and personal income – particularly the portion from “pass-through” businesses filing under the personal income tax code and taxes on investment income – are extremely volatile, relative to taxes on sales and property taxes. For instance, using data from the U.S. Census Bureau’s State Tax Collection Survey, we see that during the Great Recession, North Dakota’s corporate income tax collections fell by more than 5% and personal income tax collections fell by more than 1.5%, all in short order. Over the same period, general sales tax collections fell by less than 0.05%.

For perspective, the same Census Bureau data show 2016 severance tax revenues accounted for 41.7% of total state revenues, sales taxes for 27.4%, personal income tax for 9.46% and corporate income tax for 2.7%.

North Dakota’s experience here is not much different from the nation as a whole. As we can see in the figure of data from across all states, during the Great Recession, individual income and corporate income tax collections declined substantially, while the decline in sales tax revenues was smoother and to a lesser extent.

To summarize the literature: taxes on income and capital stunt economic growth and destabilize state budgets. And among taxes on income, flat taxes are less harmful to growth than progressive systems.

Shifting state revenue collection away from reliance on wage income, investment income and business income ensures that when the economy enters a recession – characterized by a drop in aggregate wage income due to exacerbated unemployment, depressed business revenues and poor performance of investments – state tax revenues have a softer decline than they otherwise would.

Stable, predictable revenues allow policymakers to allocate funding based on long-term needs and where it will have the greatest impact. Further, when a recession does hit, and revenues fall, they will fall more slowly and more predictably, ensuring the provision of core government services while giving lawmakers more latitude to prioritize funding.

Speaking broadly, North Dakota is well positioned to adopt pro-growth reforms to its tax code. North Dakota’s low tax rates on personal and corporate income both rank in the 10 lowest nationwide. As I noted earlier, taxes on consumption are the least distortive. So naturally, a tax on consumption, with as broad and sensible a base as possible, allows the rate to be as low as possible. Diversification for minimizing risk might work with investing, but not with taxation, largely due to the distortive nature of certain taxes. Having a code with many forms of taxes, does not increase revenue stability in the down years – rather, it injects volatility. A simple, fair tax code not only simplifies paperwork and lowers compliance costs for taxpayers, but also reduces tax avoidance behavior and lowers collection costs for government.

In the competition for resources and residents, you can fall behind simply by standing still. And there is great momentum for tax reform across the nation. In just the last five years, more than 30 states have made significant pro-growth policy changes that have provided billions of dollars in broad-based tax relief for their citizens.

The Rich States, Poor States: ALEC-Laffer Economic Competitiveness Index is a roadmap to economic growth based on free-market fiscal policy reform. The report presents rankings of the 50 states based on the relationship between policies and performance. Its economic outlook rankings are based on 15 equally-weighted economic policy variables, including tax rates, labor policy and the regulatory climate.

States that keep taxes low, avoid job-killing over-regulation and follow prudent budget practices, consistently outperform their highly taxed, over-regulated counterparts. And these policies affect where businesses and individuals choose to locate.

What about Kansas?

Of course, even with all of the positive economic data from the many successful state tax reforms, some opponents of tax reform might suggest the 2012 Kansas tax cuts prove tax reform does not produce growth. In reality, the Kansas tax reform story is far from the abject failure some like to suggest. In fact, recent data suggest there were some very positive trends for hardworking taxpayers in Kansas before taxes were subsequently raised.

Perhaps the most important complexity to keep in mind is the Kansas tax reform plan was never fully implemented as intended. Many political compromises gave us the fiscal policy patchwork that Kansas taxpayers now face. Taxes were lowered, but spending was not. Then, taxes were raised in a significant way. Some of the tax increases came in the form of broad-based retail sales taxes, while others were discriminatory taxes on consumers of specific products.

Many critics of the Kansas tax reform experience are quick to point to relatively lackluster economic growth and budget shortfalls in the years following tax reform as proof of the reforms’ failure. However, like many other states at the time, the significant downturn in oil prices and agriculture prices hit Kansas especially hard. Controlling for these sectors, the rest of the Kansas economy enjoyed growth.

Kansas provides a number of important lessons. Most notably, broad-based tax relief must be paired with responsible prioritization of spending. After all, taxes and spending are opposite sides of the same fiscal coin. Much of the criticism about Kansas is based on preconception and myth, rather than empirical data. Pro-growth tax relief can be trusted to make states more competitive, but it takes time to develop and must be offset with appropriate spending reforms.

As I wrap up my thoughts today, it is important to reiterate that tax policy has the power to make or break a state’s economic competitiveness. Overall, the economic evidence clearly showcases the success of states that have enacted pro-growth tax reforms. The 50 “laboratories of democracy” give us numerous examples of this every year.

Thank you for allowing me to share this information today. I hope this non-partisan research and analysis aids you in devising the best path to maintaining the great prosperity North Dakota has enjoyed in recent years.

I look forward to answering any questions.